"A Contract with God" (1978)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ "It is not in the heavens, that you should say, "Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?" (...) No, the thing is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart, to observe it". Deuteronomy

30 de novembro de 2014

29 de novembro de 2014

Vida

An underwater shot of a great white shark captured using a towed underwater camera off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa

28 de novembro de 2014

27 de novembro de 2014

26 de novembro de 2014

O Mal

The Banality of Evil: The Demise of a Legend

By Richard Wolin | Fall 2014

There

have been few phrases that have proved as controversial

as the famous subtitle Hannah Arendt chose to sum up her account of the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann. From the moment the articles that eventually comprised her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil were published in The New Yorker, the idea that the execution of the Nazis’ diabolical plans for an Endlösung to the “Jewish Question” could be considered “banal” offended many readers. In addition, Arendt took what seemed to be a gratuitous swipe at the conduct of the Jewish councils, which, operating under conditions of extreme duress, were forced to bargain with their Nazi overseers in the desperate hope of buying time, sacrificing some Jewish lives in the hope of saving others. Only with the benefit of hindsight do we realize that their efforts were largely futile. In her rush to judgment, Arendt made it seem as though it was the Jews themselves, rather than their Nazi persecutors, who were responsible for their own destruction. Thus, with a few careless rhetorical flourishes, she established an historical paradigm that managed simultaneously to downplay the executioners’ criminal liability, which she viewed as “banal” and bureaucratic, and to exaggerate the culpability of their Jewish victims.

as the famous subtitle Hannah Arendt chose to sum up her account of the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann. From the moment the articles that eventually comprised her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil were published in The New Yorker, the idea that the execution of the Nazis’ diabolical plans for an Endlösung to the “Jewish Question” could be considered “banal” offended many readers. In addition, Arendt took what seemed to be a gratuitous swipe at the conduct of the Jewish councils, which, operating under conditions of extreme duress, were forced to bargain with their Nazi overseers in the desperate hope of buying time, sacrificing some Jewish lives in the hope of saving others. Only with the benefit of hindsight do we realize that their efforts were largely futile. In her rush to judgment, Arendt made it seem as though it was the Jews themselves, rather than their Nazi persecutors, who were responsible for their own destruction. Thus, with a few careless rhetorical flourishes, she established an historical paradigm that managed simultaneously to downplay the executioners’ criminal liability, which she viewed as “banal” and bureaucratic, and to exaggerate the culpability of their Jewish victims.

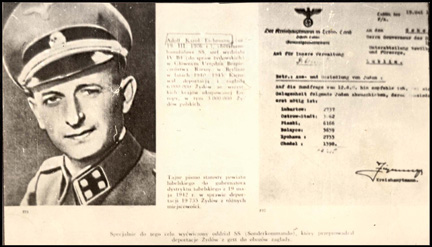

Adolf Eichmann, in an official SS photo, ca. 1942. (Courtesy of Yad Vashem Photo Archives.)

Arendt’s astonishing conclusion that “Eichmann had no criminal

motives,” and the account that underlay it, might have been construed as

mere journalistic overstatement, but her status as a distinguished

political theorist, together with the furious controversy her account

engendered—Gershom Scholem famously accused her of lacking ahavat yisrael (love for her fellow Jews)—helped to create an aura of brave truth-telling that has surrounded Eichmann in Jerusalem ever since. This image of Eichmann in Jerusalem

as an act of an intellectual bravado, with Arendt herself cast in the

role of an imperiled heroine—a latter-day Joan of Arc, persecuted by an

army of inferior male detractors—was canonized in the recent and widely

praised German film by Margarethe von Trotta, Hannah Arendt.

It is certainly true that throughout the controversy Arendt comported

herself as someone who was above the fray. Often she seemed to regard

the Israelis she encountered in Jerusalem with as little esteem as she

did Eichmann. She dismissed the chief prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, with

breathtaking condescension as a “typical Galician Jew, very

unsympathetic, boring, constantly making mistakes. Probably one of those

people who don’t know any languages.” While covering the trial she

wrote to her former mentor, the philosopher Karl Jaspers:

Everything is organized by a police force that gives me the creeps,

speaks only Hebrew and looks Arabic. Some downright brutal types among

them. They would obey any order. And outside the doors, the oriental

mob, as if one were in Istanbul or some other half-Asiatic country. In

addition, and very visible in Jerusalem, the peies [sidelocks] and caftan Jews, who make life impossible for all reasonable people here.

Even setting aside the egregious racism and anti-Jewish animus, there

is something very alarming about this passage. Any reader familiar with

Arendt’s classic study The Origins of Totalitarianism knows that

she described such mobs as the carriers of the totalitarian bacillus.

Nor can there be any mistaking the import of her assertion that the

Sephardic or Mizrahi policemen “would obey any order.” With this claim,

Arendt insinuated that they were the “authoritarian personalities” and

“desk murderers” of the future. Again and again, one sees how readily

Arendt blurred the line between victims and executioners.

Arendt’s banality thesis helped to engender the so-called

“functionalist” interpretation of the Holocaust, in which the role of

obedient desk murderers and mindless functionaries assumed pride of

place. Leading German historians such as Hans Mommsen coined nebulous

phrases such as “cumulative radicalization” in order to describe a

killing process that, like a Betriebsunfall (an industrial

accident), seemed to have happened without anyone consciously willing

it. But as the historian Ulrich Herbert has pointed out, at the time the

functionalist account was also culturally convenient: “For a long time

there was a reluctance to name names in research on National Socialism .

. . [Consequently,] there was also massive resistance to studies about

the perpetrators and their relationship to German society.” The upshot

of this approach was that the Holocaust’s character as a crime conceived

and masterminded by German anti-Semitic ideologues that was perpetrated

against the Jews disappeared in favor of a series of conceptual

abstractions—“modernity,” “bureaucracy,” “mass society”—in which the

Jewish (or anti-Jewish) specificity of the events in question all but

disappears.

Was Eichmann, or the evil he was instrumental in perpetrating, really banal?

Remarkably, it seems that Arendt had already arrived at a definitive

judgment of Eichmann’s character some four months before the trial even

began. In another letter to Jaspers, written on December 2, 1960, she

writes that the upcoming trial would offer her the opportunity “to study

this walking disaster [i.e., Eichmann] face to face in all his bizarre vacuousness.” But, as Bettina Stangneth shows in her well-researched and path-breaking study Eichmann Before Jerusalem,

Eichmann was, in fact, a consummate actor. “Eichmann,” she writes,

“reinvented himself at every stage of his life, for each new audience

and every new alarm.” He becomes “subordinate, superior officer,

perpetrator, fugitive, exile, and defendant.”

The meek and unassuming Argentine rabbit breeder who took the witness

stand in Jerusalem and described himself as “a small cog in Adolf

Hitler’s extermination machine” bore no resemblance to the man who, as

Specialist for Jewish Affairs of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA),

reported directly to Heinrich Himmler and had avidly sown terror and

destruction throughout the lands of Central Europe. Nor did he resemble

the man who, under the alias of Ricardo Klement, had been the toast of

Argentina’s highly visible neo-Nazi community, the man who unabashedly

signed photographs for fellow fugitives: “Adolf Eichmann, SS Obersturmbannführer

(retired).” As Stangneth aptly observes, “Eichmann-in-Jerusalem was

little more than a mask.” Eichmann gave the performance of his life, and

Hannah Arendt was entirely taken in.

In Jerusalem, Eichmann fought to save his life, and, if possible, to

clear his name for posterity. But another one of his central motivations

was to throw a monkey wrench into the gears of the Israeli judicial

apparatus, whose staff he regarded as his Jewish “persecutors.” During

his proud years in the SS, combating the pernicious influence of World

Jewry had been Eichmann’s raison d’être. With his artful performance on

the witness stand in Jerusalem, Eichmann, ever the warrior, was, in

effect, making his final stand. True to the SS creed of loyalty above

all (“Mein Ehre heisst Treue”), he went down fighting.

It has long been known that the CIA had been privy to Eichmann’s

whereabouts after the war. Hence it was with the CIA’s tacit approval

that, in 1950, Eichmann, in order to avoid capture, successfully made

use of the notorious “rat line” to South America. Only a few years ago,

it came to light that the German Intelligence Services had also been

well aware of Eichmann’s various activities prior to his flight to South

America. German officials also refused to lift a finger, but, for

slightly different reasons. Eichmann, it seemed, knew too much about

prominent ex-Nazis who had recently been elevated to the status of

“notables”—politicians, opinion leaders, and scholars—in the newly

conceived Federal Republic. His apprehension, they believed, would have

injured the emerging German democracy. As Stangneth remarks laconically,

although the trappings of constitutional democracy had been freshly

implanted on German soil, the problem was that “there were no new people

to administer them.”

One of the main reasons that Arendt’s banality of evil concept struck a nerve

was that it played on widespread fears about the dehumanizing effects

of “mass society.” When she wrote about Eichmann, the Nazi threat was

past, but, in the war’s aftermath, an arguably greater menace had

arisen, the threat of nuclear annihilation. This threat had been vividly

driven home by the Cuban missile crisis, which took place the year

before Arendt’s articles on the Eichmann trial were serialized in The New Yorker. It was tempting and superficially plausible to interpret both events as expressions of the same general phenomenon.

But to state a truism: Mass society can be dehumanizing without its denizens being mass murderers. In his magisterial study Nazi Germany and the Jews

Saul Friedländer describes the mentality of “redemptive anti-Semitism”

that pervaded Nazi rule from its inception. What is needed to turn

bureaucratic specialists into executioners is an ideological world view

that underwrites racial supremacy and terror. This is the indispensable

component that Nazism furnished and that, during the 1930s, reoriented

Germany as a society hell-bent on military aggression, imperial

expansion, and racial purification. One of the outstanding merits of

Stangneth’s comprehensive account is that she shows that Eichmann was

anything but a faceless cog in the machine. He fully subscribed to the

ideological goals of the regime, including mass murder.

From the very beginning, Eichmann was a firm believer in the

existence of a Jewish world conspiracy and thus fully partook of the

murderous ethos so well described by Friedländer. In Eichmann’s view,

the elimination of World Jewry, far from being a matter-of-fact,

bureaucratic assignment, was a sacred duty. During one of Eichmann’s

visits to Auschwitz, commandant Rudolf Höss confided that, upon seeing

Jewish children herded into the gas chambers, his knees quivered,

whereupon Eichmann rejoined that it was precisely the Jewish children

who must be first sent into the gas chambers in order to ensure the

wholesale elimination of the Jews as a race.

In a hastily contrived farewell speech to his subordinates at the end

of the war, Eichmann declared that he would die happy, knowing that he

was responsible for the deaths of millions of European Jews:

I will laugh when I leap into the grave because I have the feeling that I have killed 5,000,000 Jews. That gives me great satisfaction and gratification.

Twelve years later, in the course of the alcohol-infused colloquies

with a group of fugitive Nazis in Buenos Aires whose transcripts are one

of Stangneth’s key sources, he said: “To be frank with you, had we

killed all of them, the thirteen million, I would be happy and say: ‘all

right, we have destroyed an enemy.’”

To describe such a person as merely a man of “revolting stupidity” (von empörender Dummheit),

as though his lack of intelligence somehow made his status as a

genocidal murderer comprehensible, as Hannah Arendt did in the course of

a 1964 interview, is perilously myopic. It was as though, by alluding

to Eichmann’s purported intellectual failings, Arendt could make all

other substantive questions and issues disappear. Perversely, the Jewish

Specialist for the Reich Security Main Office ended up having the last

laugh, hoodwinking Arendt into believing that he was little more than a

bit player on a larger political stage. Yet, in the Jewish émigré press

during the late 1930s (which Stangneth believes that Arendt had read),

Eichmann had already been known as the “Tsar of the Jews” and was

notorious for his brutality. But Arendt had her own intellectual agenda,

and perhaps out of her misplaced loyalty to her former mentor and

lover, Martin Heidegger, insisted on applying the Freiburg philosopher’s

concept of “thoughtlessness” (Gedankenlosigkeit) to Eichmann. In doing so, she drastically underestimated the fanatical conviction that infused his actions.

By underestimating Eichmann’s intellect, Arendt also misjudged the

magnitude of his criminality. Yet, as Stangneth demonstrates

convincingly, in cities across the continent, Eichmann proved himself to

be a persistent and effective negotiator, and when he failed to acquire

what he demanded by way of negotiations, he was adept at using threats.

Thus with a relatively small staff at his disposal, Eichmann

systematically forced Jews out of their residences and into makeshift

ghettos. As the Final Solution began, he arranged for their

long-distance transport to the far reaches of provincial Poland, where

the extermination camps lay in wait. As Raul Hilberg, on whose findings

Arendt relied extensively, observed:

[Arendt] did not discern the pathways

that Eichmann had found in the thicket of the German administrative

machine for his unprecedented actions. She did not grasp the dimensions

of his deed. There was no “banality” in this “evil.”

To amplify what she meant by the banality of evil, Arendt invoked the

concept of “administrative murder,” which, in keeping with the robotic

portrait she had painted of Eichmann, was another way of establishing

the primacy of the functionary or desk murderer. But there had been

nothing in the least “administrative” or “banal” about the barbaric mass

shootings of the Einsatzgruppen—whose signature was the infamous Genickschuss

(shot in the nape of the neck)—as led by the SS’s notorious “Death’s

Head” brigades in the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. These deaths

occurred prior to the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, in which the

logistics of the Final Solution were outlined.

Eichmann’s organizational talents became especially vital and

indispensable in the case of the deportation and extermination of

565,000 Hungarian Jews during the waning years of the war. The Hungarian

situation was especially tricky. Even though the 1943 Warsaw ghetto

uprising had been successfully and brutally suppressed by the SS, it had

exposed a weakness in the Nazi machinery of extermination. In addition,

the RSHA had failed in its attempts to deport Denmark’s meager total of

less than 8,000 Jews. Following D-Day, it had become clear that, from a

German standpoint, the war was unwinnable. Thereafter, numerous

individual Nazi potentates sought to scale back the Jewish deportations

in the hope of receiving favorable treatment from the

soon-to-be-victorious Allies. But as Stangneth shows, Eichmann would

have none of it. In fall 1944, he went so far as to defy Himmler’s order

to halt the Hungarian deportations. Moreover, he played an especially

insidious role in overseeing the “death marches” of the remaining

Hungarian Jews (some 400,000 had already been transported to Auschwitz),

under conditions that were indescribably brutal.

As Germany’s military situation began to deteriorate, Eichmann showed

himself especially adept at ensuring that the gears of the killing

machine remained well oiled. To characterize Eichmann as a “desk

murderer” in order to downplay his convictions as a devoted SS officer

who reported directly to Reinhard Heydrich and Gestapo chief Heinrich

Müller is seriously misleading. After all, the duties of office demanded

that Eichmann regularly visit various killing sites.

In 1998, an immense transcript of Eichmann’s conversations with Dutch

collaborator and Waffen SS officer Willem Sassen from the late 1950s in

Argentina was mysteriously deposited in the German Federal Archive in

Koblenz. In those conversations, Eichmann told Sassen “When I reached

the conclusion that it was necessary to do to the Jews what we did, I

worked with the fanaticism a man can expect from himself.” He seems to

have had in mind Heinrich Himmler’s statement of the requirements of

total ideological commitment within the SS at the very height of the

extermination process:

These measures in the Reich cannot be

carried out by a police force made up solely of bureaucrats. … A corps

that had merely sworn an oath of allegiance would not have the necessary

strength. These measures could be borne and executed only by an extreme

organization of fanatic and deeply convinced National Socialists. The

SS regards itself as such and declares itself as such, and therefore has

taken the task upon itself.

How Arendt could believe that someone like Eichmann could thrive in

an organization whose raison d’être was mass murder, shorn of the

ideological zeal described by Himmler, is difficult to fathom. Yet, time

and again, in defiance of all evidence to the contrary, she maintained

that Eichmann could best be described as a mere “functionary.” “I don’t

believe that ideology played much of a role,” Arendt repeatedly

insisted, “to me that appears to be decisive.”

In this respect, Arendt’s findings dovetailed with ageneral trend in

accounts of the Holocaust that downplayed the role of individual

perpetrators in favor of the impersonal “structures” of modern society.

But white-collar workers and “organization men” do not as a matter of

course commit mass murder unless they are in the grip of an

all-encompassing, exterminatory world view, such as the Nazi credo that

SS officers were obligated to internalize. As Walter Laqueur noted

during the late 1990s: Arendt’s “concept of the ‘banality of evil’ . . .

made it possible to put the blame for the mass murder at the door of

all kind of middle level bureaucrats. The evildoer disappears, or

becomes so banal as to be hardly worthy of our attention, and is

replaced by . . . underlings with a bookkeeper mentality.”

In seeking to downplay the German specificity of the Final Solution

by universalizing it, Arendt also strove to safeguard the honor of the

highly educated German cultural milieu from which she herself hailed. A

similar impetus underlay Arendt’s contention, in her contribution to the

Festschrift for Heidegger’s 80th birthday, that Nazism was merely a

“gutter-born phenomenon” and had nothing to do with the spiritual

(geistige) questions of culture. In light of what we now know about the

extent of educated German support for the regime (not to speak of what

we know about Heidegger, on which see my earlier essay “National Socialism, World Jewry, and the History of Being: Heidegger’s Black Notebooks”

in this magazine) Arendt’s notion that Nazism has nothing to do with

the “language of the humanities and the history of ideas” appears naïve.

In retrospect, Arendt’s application of Heidegger’s concept of

“thoughtlessness” to Eichmann and his ilk seems to have been intended to

absolve the German intellectual traditions. Even Arendt’s otherwise

stalwart champion, Mary McCarthy, pointed out the crucial differences

between the English word “thoughtlessness,” which suggests a boorish

absent-mindedness, and the German Gedankenlosigkeit, which literally indicates an inability to think.

At the height of his danse macabre before the judicial

tribunal in Jerusalem, Eichmann went so far as to characterize himself

as a “Zionist,” on the basis of his negotiations during the

1930s with Jewish officials over the emigration of Viennese and Czech

Jews. For her part, Arendt seemed to buy Eichmann’s self-serving

self-description wholesale. Yet, as Stangneth shows, these forced

emigrations organized by Eichmann were unfailingly sadistic and brutal.

In retrospect, they were, in fact, a trial run for the Europe-wide

Jewish deportations that culminated in the Final Solution. Thus under

Eichmann’s supervision and under the cover of “emigration,” Jews were

divested of their homes, their life savings, their possessions, their

livelihood, and their citizenship in exchange for the uncertainties and

ignominies of forced exile.

That Eichmann smugly viewed his indispensable role in the Final

Solution as a crowning achievement was an opinion he expressed on

numerous occasions. British historian David Cesarani aptly describes the

RSHA Nazi’s Specialist for Jewish Affairs as acting “in the spirit of a

fanatical anti-Semite who is locked in a world of fantasy,” a

description that historian Christopher Browning recently seconded,

noting that, “Eichmann embraced a worldview that was delusional and

‘phantasmagoric’ in its belief in a world Jewish conspiracy that was the

implacable and life-threatening enemy of Germany.” When the regime imploded in May 1945, he became a warrior-without-a-cause.

As Stangneth shows, during his Argentine exile, Eichmann and his Nazi

comrades harbored delusions of the Reich’s return. At the time, one of

Eichmann’s pet literary projects was the drafting of an “open letter” to

Konrad Adenauer that was intended to justify the National Socialist

state and its aims. In Eichmann’s view, the Federal Republic should have

stopped issuing apologies since it had nothing to be ashamed of. After

all, during the war, Germany had been involved in a life-or-death

struggle in which it had been necessary to employ all of the means at

its disposal. As Eichmann was fond of saying: “Krieg ist Krieg”—war is war.

In Buenos Aires, the Sassen clique published a neo-Nazi journal, one

of whose main aims was to burnish the reputation of the Third Reich in

the face of “calumnious accusations” on the part of World Jewry.

Foremost among those purported “calumnies” was the so-called “Auschwitz

lie”: the “myth” that the Third Reich had been responsible for the

deaths of six million Jews. It was for this reason that, in 1956, the

former Dutch SS officer Willem Sassen conducted a series of interviews

with Eichmann. After all, there could be no more convincing witness than

Eichmann, who, from his perch at RSHA headquarters in Berlin, had

dutifully and conscientiously organized the entire affair.

Yet along the way, Sassen and company encountered a stumbling block.

On the one hand, Eichmann being Eichmann, he was more than willing to

relive in minute detail his halcyon days in Division IV B of the Reich

Security Main Office. The problem was that the destruction of European

Jewry had been Eichmann’s proudest achievement.

By the end of the taping sessions, the mismatch between Sassen’s

revisionist goals and Eichmann’s compulsive braggadocio reached absurd

proportions. The misunderstanding culminated in a raucous 1957 meeting

at which Eichmann felt compelled to provide a final statement to all

assembled of his mature ideological world view. Here are three salient

passages from Eichmann’s final declaration to Sassen and company:

I must throw all caution to the wind and

tell you that, before my Volk goes to ruin and bites the dust, the whole

world should go to ruin and bite the dust—my Volk, only thereafter!

I say to you honestly as we conclude our

sessions, I was the “conscientious bureaucrat,” I was that indeed. But I

would hereby like to expand on the idea of the “conscientious

bureaucrat,” perhaps to my discredit. Within the soul of this

conscientious bureaucrat lay a fanatical warrior for the freedom of the

race from which I stem . . . I was manifestly a conscientious

bureaucrat, but one who was driven by inspiration: what my Volk requires

and my Volk demands is for me a holy commandment and a holy law. Jawohl!

But now let me tell you, since we are almost at the end of this entire outburst [Platzen]

. . . : I regret nothing! I will never crawl my way to the cross! . . .

That is something I cannot do . . . because my inner self bridles at

the thought that we did something wrong. No, I say to you quite

honestly, had we killed 10.3 million Jews out of the 10.3 million we had

in our sights, I would be quite satisfied, and would say that we

annihilated an enemy . . . We would have fulfilled our mission, for our

race and our Volk and for the freedom of nations, had we exterminated

the cleverest spirit among the spirited peoples alive today. For that is

what I told [Julius] Streicher, and what I have always preached: we are

fighting against an opponent who, as a result of thousands of years of

practice and experience, is cleverer than we are . . .

These are the words not of a “desk murderer” but of a convinced Nazi.

They represent a toxic admixture of crude social Darwinism, malicious

half-truths, and ideological distortions. The highest reality is that of

the volk. Weak peoples perish. The strong survive. All pretensions of

international law to the contrary, it is the survival of the fittest

that determines the “law of peoples.” Since, as with all of life, the

goal of nations is self-preservation, it is permissible to utilize all

the means at one’s disposal to attain this end. Any volk that ignores

this imperative is doomed to extinction. Universal morality—Biblical

injunctions (“Thou shalt not kill,” “Love thy neighbor as thyself”),

Kant’s categorical imperative, democratic pretensions to universal

equality—must be emphatically rejected insofar as such effete

considerations expose a people to anti-völkisch precepts and

constraints that threaten to sap its lifeblood, its will to survive. To

cite Nietzsche, whose influence Eichmann at various points acknowledged,

moral considerations that transcend a volk’s drive to self-preservation

are symptomatic of a “slave morality.” If nature has decreed that life

is in essence a fight to the death for racial supremacy, what sense does

it make to buck this trend?

In Eichmann’s view, one of the reasons why the Jews, those consummate

cosmopolitans, are so dangerous is that, as a people without roots,

they subsist and persevere entirely at the expense of other peoples. For

this reason, they are the sworn racial enemy of the Germans as well as of all peoples. Hence, the National Socialist Vernichtungskrieg (war of annihilation) against the Jews was, on racial grounds, entirely justified.

Insofar as they are impervious to reason and reality, such

mythological world views are self-perpetuating. The clan of believers

has a vested interest in maintaining the illusion that the world view is

entirely coherent and functional, since there is really no fallback

position. Nazi ideology was an all-enveloping proposition. It only

collapsed when, at the war’s end, the major German cities lay in ruins

and Germany had become, following Hitler’s suicide, a führerlose Gesellschaft:

a society without a leader. It is therefore difficult to understand

how, shortly after the trial, Arendt, speaking of Eichmann’s actions and

conduct, could assert, “I don’t think that ideology played any role.” A

decade earlier, the chapters on “Ideology” and “Race” had been among

Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism’s genuine strong points.

If ever there was a “trial of the 20th century,” the Eichmann trial was it.

In Europe and North America, the meaning of the trial, and thus to a

great extent the Holocaust itself, was filtered through the lens of

Arendt’s popular account and the contentious debate that it spawned. Her

provocative subtitle, the “banality of evil,” helped establish the

so-called “functionalist” interpretation of the Holocaust, in which the

role of obedient desk murderers and mindless functionaries assumed pride

of place, producing a Holocaust strangely divested of anti-Semitism.

The reductio ad absurdum of this approach may have finally come during the controversy over Daniel Goldhagen’s book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. In

the course of this debate, in the 1990s, Hans Mommsen, by then the

recognized dean of German Third Reich scholars, said, “I don’t think the

perpetrators were really clear in their own minds about what they were

doing when they were engaged in killing Jews.” Mommsen’s avowal was

widely viewed as an index of how far out of touch professional

historians were with the German public’s need for clarity and for an

honest accounting of a previous generation’s horrific transgressions. In

retrospect, Arendt’s stress on the perpetrators’ lack of animosity

toward the Jews harmonized with the post-war German political agenda of

parrying questions of historical responsibility. Although Arendt did not

necessarily share this agenda, her correspondence reveals how sensitive

she was to the tendency to equate “Germans” with “Nazis.”

Although Arendt’s interpretive approach, as well as the functionalist

paradigm in general, identified a set of important socio-historical

concerns, it also downplayed the uniqueness of the Shoah by inserting it

within an overarching narrative that highlighted the dangers of

“modernity,” “mass society,” “atomization,” and so on. The Holocaust

came to symbolize the risks of the transition from traditional society

to the modern administrative state. But in the end this German Sociology

101 “from Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft” approach failed

to explain the historical uniqueness of the radical evil that was Nazi

Germany. Here, one of the unexplained paradoxes and ironies was that in The Origins of Totalitarianism the

figure of radical evil occupied pride of place in Arendt’s interpretive

scheme. In fact, she concluded the book’s Preface by declaring: “if it

is true that in the final stages of totalitarianism an absolute evil appears

(absolute because it can no longer be deduced from humanly

comprehensible motives), it is also true that without it we might never

have known the truly radical nature of Evil.”

As Bettina Stangneth reminds us repeatedly in Eichmann Before Jerusalem,

when Hannah Arendt traveled to Jerusalem to cover the Eichmann trial,

part of the baggage she carried was a fixed set of socio-historical

predispositions and prejudgments. Nowhere was this problem more evident

than in her attempt to understand Eichmann’s conduct in terms of the

misguided figure of the “banality of evil.” What should have been clear

then and should certainly be clear now is that if the Holocaust was

banal, then it was not evil. And if it was evil—as it indubitably

was—then it was not banal.

25 de novembro de 2014

Vida

A nudibranch (Limacia clavigera) searching for food on algae in the North East Atlantic Ocean (Gulen, Norway)

The Ḥaliẓah Shoe

The

ceremony of the taking off of a brother-in-law's shoe by the widow of a

brother who has died childless, through which ceremony he is released

from the obligation of marrying her,

and she becomes free to marry whomever she desires (Deut. xxv. 5-10).

and she becomes free to marry whomever she desires (Deut. xxv. 5-10).

24 de novembro de 2014

Morte

Patio civil, cementero San Rafael, Malaga, 2009

70 years after the end of the Spanish Civil War, Luc Delahaye

photographed the forensic exhumation of a mass grave containing the

bodies of executed Republican prisoners

23 de novembro de 2014

22 de novembro de 2014

21 de novembro de 2014

20 de novembro de 2014

19 de novembro de 2014

18 de novembro de 2014

Har Nof Synagogue Terror Attack

Five Israelis were killed in a frenzied assault by two Palestinians who targeted worshippers at a Jerusalem synagogue.

"Letters to Afar"

"Letters to Afar", Installation by Péter Forgács and The Klezmatics,

a new exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York.

The video art installation is based on films taken by Jewish immigrants

who traveled from New York back to Poland during the 1920s and 1930s.

With few exceptions, this is the only motion picture documentary record

of Jewish life in prewar Poland.

17 de novembro de 2014

The Science of Suffering

Kids are inheriting their parents' trauma. Can science stop it?

By Judith Shulevitz, "New Republic"

Lowell,

Massachusetts, a former mill town of the red-brick-and-waterfall

variety 25 miles north of Boston, has proportionally more Cambodians and

Cambodian-Americans than nearly any other city in the country: as many

as 30,000, out of a population of slightly more than 100,000. These are

largely refugees and the families of refugees from the Khmer Rouge, the

Maoist extremists who, from 1975 to 1979, destroyed Cambodia’s economy;

shot, tortured, or starved to death nearly two million of its people;

and forced millions more into a slave network of unimaginably harsh

labor camps. Lowell’s Cambodian neighborhood is lined with dilapidated

rowhouses and stores that sell liquor behind bullet-proof glass,

although the town’s leaders are trying to rebrand it as a tourist

destination: “Little Cambodia.”

At

Arbour Counseling Services, a clinic on a run-down corner of central

Lowell, 95 percent of the Cambodians who come in for help are diagnosed

with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD. (In Cambodia itself, an

estimated 14.2 percent of people who were at least three years old

during the Pol Pot period have the disorder.) Their suffering is

palpable. When I visited Arbour, I met a distraught woman in her forties

whom I’ll call Sandy. She was seven when she was forced into the jungle

and 14 when she came to the United States, during which time she lived

in a children’s camp, nearly starved to death, watched as her father was

executed, and was struck in the ear by a soldier’s gun. She

interspersed her high-pitched, almost rehearsed-sounding recitation of

horrors past with complaints about the present. She couldn’t

concentrate, sleep at night, or stop ruminating on the past. She “thinks

too much,” a phrase that is common when Cambodians talk about PTSD.

After she tried to kill herself while pregnant, her mother took Sandy’s

two daughters and raised them herself. But they have not turned out

well, in Sandy’s opinion. They are hostile and difficult, she says. They

fight their grandmother and each other, so bitterly that the police

have been called. They both finished college and one is a pharmacist and

the other a clerk in an electronics store. But, she says, they speak to

her only to curse her. (The daughters declined to talk to me.)

On

the whole, the children of Cambodian survivors have not enjoyed the

upward mobility of children of immigrants from other Asian countries.

More than 40 percent of all Cambodian-Americans lack a high school

diploma. Only slightly more than 10 percent have a bachelor’s degree.

The story of Tom Sun, a soft-spoken, pop-star-dapper thirtysomething (he

doesn’t know his exact age) is emblematic, except, perhaps, in how well

he’s doing now. His mother was pregnant with him during the Khmer Rouge

years. His father died before the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia and drove

the Khmer Rouge back into the jungle. When he was very young, he, his

mother, and a little brother made their way from a Thai refugee camp to

the United States and eventually settled in Lowell. The two boys and two

other brothers, born after they arrived in the United States, were left

to raise themselves. Illiterate and shattered, their mother gambled,

cried, and yelled at her sons. “My mother, she’s loud,” Sun told me.

“She’s got a very mean tone. I still hear it in my head.” His

stepfather, a mechanic, also a survivor and also illiterate, beat them

until welts striped their bodies. By the time Sun should have entered

seventh grade, he had joined the Tiny Rascals, perhaps the largest Asian

American street gang in the United States. “It was comforting,” he

says. “We weren’t into drugs or alcohol.” They were into being a

substitute family. They were also into guns. Sun was involved in a

shooting that led to a stint in prison, which led to a GED, some college

credits, and some serious reflection on his future. He left the gang in

his mid-twenties. His brothers were not so lucky. Two of them are

serving life sentences for murder.

The

children of the traumatized have always carried their parents’

suffering under their skin. “For years it lay in an iron box buried so

deep inside me that I was never sure just what it was,” is how Helen

Epstein, the American daughter of survivors of Auschwitz and

Theresienstadt, began her book Children of the Holocaust,

which launched something of a children-of-survivors movement when it

came out in 1979. “I knew I carried slippery, combustible things more

secret than sex and more dangerous than any shadow or ghost.” But how

did she come by these things? By what means do the experiences of one

generation insinuate themselves into the next?

Traditionally,

psychiatrists have cited family dynamics to explain the vicarious

traumatization of the second generation. Children may absorb parents’

psychic burdens as much by osmosis as from stories. They infer

unspeakable abuse and losses from parental anxiety or harshness of tone

or clinginess—parents whose own families have

been destroyed may be unwilling to let their children grow up and leave

them. Parents may tell children that their problems amount to nothing

compared with what they went through, which has a

certain truth to it, but is crushing nonetheless. “Transgenerational

transmission is when an older person unconsciously externalizes his

traumatized self onto a developing child’s personality,” in the words of

psychiatrist and psychohistorian Vamik Volkan. “A child then becomes a

reservoir for the unwanted, troublesome parts of an older generation.”

This, for decades, was the classic psychoanalytic formulation of the

child-of-survivors syndrome.

But researchers are increasingly painting a picture of a psychopathology so fundamental, so, well, biological, that efforts to talk it away can seem like trying to shoot guns into a continent, in Joseph Conrad’s unforgettable image from Heart of Darkness.

By far the most remarkable recent finding about this transmogrification

of the body is that some proportion of it can be reproduced in the next

generation. The children of survivors—a surprising number of them, anyway—may

be born less able to metabolize stress. They may be born more

susceptible to PTSD, a vulnerability expressed in their molecules,

neurons, cells, and genes.

After a

century of brutalization and slaughter of millions, the corporeal

dimension of trauma gives a startling twist to the maxim that history

repeats itself. Yael Danieli, the author of an influential reference

work on the multigenerational dimensions of trauma, refers to the

physical transmission of the horrors of the past as “embodied history.”

Of course, biological legacy doesn’t predetermine the personality or

health of any one child. To say that would be to grossly oversimplify

the socioeconomic and geographic and irreducibly personal

forces that shape a life. At the same time, it would be hard to

overstate the political import of these new findings. People who have

been subject to repeated, centuries-long violence, such as African

Americans and Native Americans, may by now have disadvantage baked into

their very molecules. The sociologist Robert Merton spoke of the

“Matthew Effect,” named after verse 25:29 of the Book of Matthew: “For

unto every one that hath shall be given ... but from him that hath not

shall be taken.” Billie Holiday put it even better: “Them that’s got

shall have; them that’s not shall lose.”

But

daunting as this research is to contemplate, it is also exciting. It

could help solve one of the enduring mysteries of human inheritance: Why

do some falter and others thrive? Why do some children reap the

whirlwind, while other children don’t? If the intergenerational

transmission of trauma can help scientists understand the mechanics of

risk and resilience, they may be able to offer hope not just for

individuals but also for entire communities as they struggle to cast off

the shadow of the past.

Rachel

Yehuda, a psychologist at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in the Bronx

and a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Mount Sinai Hospital,

has well-coiffed blonde hair, a slew of impressive post-doctoral

students, and an air of rock-solid confidence. She is the go-to person

on the molecular biology of intergenerational trauma, although she may

never have pursued this line of research were it not for the persistence

of the children of trauma victims themselves.

In

the late ’80s, when Yehuda was a postdoctoral fellow in psychology at

Yale, she was analyzing the results of an interview with a shell-shocked

Vietnam veteran. At one point, she told her mentor, “I just can’t

understand whether trauma does this, or whether this is just who this

person is.” He said, “Rachel, that is a testable hypothesis.” So she

tested it. Yehuda had grown up in Cleveland Heights outside Cleveland,

Ohio, in a Jewish neighborhood full of Holocaust survivors. She returned

home and used a university archive to identify survivors from among her

neighbors. In her initial experiments, Yehuda found that Holocaust

survivors with PTSD had a similar hormonal profile to the one she was

seeing in veterans. In particular, they had less cortisol, an important

steroid hormone that helps regulate the nervous and immune systems’

responses to extreme stress. Some of the participants have objected

strongly to the comparison: ‘“They had guns! We were hunted,”’ they’d

tell her. “But that doesn’t mean they both don’t experience nightmares,”

she says.

Trauma is generally

defined as an event that induces intense fear, helplessness, or horror.

PTSD occurs when the dysregulation induced by that trauma becomes a

body’s default state. Provoke a person with PTSD, and her heart pounds

faster, her startle reflex is exaggerated, she sweats, her mind races.

The amygdala, which detects threats and releases the emotions associated

with memories, whirs in overdrive. Meanwhile, hormones and

neurotransmitters don’t always flow as they should, leaving the immune

system underregulated. The result can be the kind of over-inflammation

associated with chronic disease, including arthritis, diabetes, and

cardiovascular disease. Moreover, agitated nervous systems release

adrenaline and catecholamines, both involved in the fight or flight

response, unleashing a cascade of events that reinforces the effects of

traumatic memories on the brain. This may partially explain the

intrusive memories and flashbacks that plague people with PTSD. Extreme

stress and PTSD also appear to shorten telomeres—the DNA caps at the end of a chromosome that govern the pace of aging.

In

the early ’90s, Yehuda opened a clinic to treat and study Holocaust

refugees. She often got calls from the children of survivors. “At first,

I would just politely explain that this is not a program for

offspring,” she says. But then she happened to read Maus,

Art Spiegelman’s now-classic graphic novel about a paranoid Auschwitz

survivor and his puzzled, repelled son, who observes that his father

“bleeds history.” Shortly thereafter, yet another survivor’s child

called her and said, “If you understood the issues better, I think you

would see that we need a program also.” “Come on by and educate me,”

Yehuda replied. The man was an Ivy League graduate and a successful

professional “whom you would not think was the casualty of anything,”

she says. She listened to him talk about his unhappy childhood for

several hours, and then stopped him. How could he square his impressive

accomplishments with the notion that he was damaged? “He said: ‘Well,

there are a lot of ways to be damaged. I wouldn’t want to be the person

involved in an intimate relationship with me. I wouldn’t trust myself to

be a good father.’” That is when Yehuda decided to research therapies

for the children of survivors, too.

She

knew some of them were troubled, but she didn’t know why. Was the

damage a function of the way they were being raised? Or was it

transmitted by some other means?

In

early papers Yehuda produced on Holocaust offspring, she discovered that

the children of PTSD-stricken mothers were diagnosed with PTSD three

times as often as members of control groups; children of fathers or

mothers with PTSD suffered three to four times as much depression and

anxiety, and engaged more in substance abuse. She would go on to

discover that children of mothers of survivors had less cortisol than

control subjects and that the same was true of infants whose mothers had

been pregnant and near the Twin Towers on 9/11.

In

the early ’90s, whenever Yehuda presented her findings, fellow

scientists scoffed at them. The prevailing wisdom then held that the

fearful body manufactures too much cortisol, not

too little, and moreover that effects of stress on the body are

fleeting. Yehuda was asserting that PTSD is correlated with lower, not

higher, cortisol levels and that this trait—and vulnerability to PTSD—could be passed from parent to child. “My colleagues did not believe me,” she says.

They

also accused her of espousing Lamarckian genetics. The

eighteenth-century thinker Jean-Baptiste Lamarck held that traits

acquired over the course of a lifetime could be bequeathed to offspring.

Evolutionary thinkers had been ridiculing his views for well over a

century. The Darwinian orthodoxy was that, while biology may be destiny,

the vicissitudes of individual fate don’t alter the underlying

sequences of genes. Yehuda told her critics: “Listen, I don’t know

what’s right or wrong. I’m telling you what it is.”

Since

then, further research offers support for Yehuda’s thesis. Studies of

twins have showed that a propensity for PTSD after trauma is about 30 to

35 percent heritable—which means that genetic

factors account for about a third of the variation between those who get

PTSD and others. More biologists are unpacking the epigenetic effects

of PTSD—how it may change the way genes express

themselves and how these changes may then reprogram the development of

offspring. For instance, the kind of PTSD to which a child may succumb

differs according to whether it was a mother or a father who passed on

the risk. Maternal PTSD heightens the chance that a child will incur the

kind of hormonal profile that makes it harder to calm down. Paternal

PTSD exacerbates the possibility that the child’s PTSD, if she gets it,

will be the more serious kind that involves feeling dissociated from her

memories. A mother’s PTSD can affect her children in so many ways—through the hormonal bath she provides in the womb, through her behavior toward an infant—that

it can be hard to winnow out her genetic contribution. But, Yehuda

argues, paternal transmission is more clear-cut. She believes that her

findings on fathers suggest that PTSD may leave its mark through

epigenetic changes to sperm.

About a

decade ago, Michael Meaney, a professor of psychiatry at McGill

University in Montreal, founded the field of behavioral epigenetics when

he proved, by experimenting with rat mothers and their pups, that early

experiences modify gene expression and that those modifications can be

passed from one generation to another. David Spiegel, a professor of

psychiatry at Stanford University and a former president of the American

College of Psychiatrists, told me that Meaney had revealed the

epigenetic transmission of vulnerability in rats, and Yehuda is now

showing it in humans. Yehuda is, he wrote in an e-mail, “ahead of her

time.”

What Yehuda hopes to do is

nothing less than untangle the web of relationships among biology,

culture, and history. Do social forces transform our biology? Or does

biology “permeate the social and cultural fiber”? How do you even begin

to tease these things apart?

Maciek Jasik

Garretson

Sherman, 30, his son Rich, 5 months, and his mother, Caroline M.

Bryant, 51, in Staten Island, New York. Weary of the chaos following

Liberia's long civil war, Garretson left the country in 2007. His

mother, who is visiting, still lives there.

In the early ’80s,

a Lakota professor of social work named Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart

coined the phrase “historical trauma.” What she meant was “the

cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and

across generations.” Another phrase she used was “soul wound.” The

wounding of the Native American soul, of course, went on for more than

500 years by way of massacres, land theft, displacement, enslavement,

then—well into the twentieth century—the

removal of Native American children from their families to what were

known as Indian residential schools. These were grim, Dickensian places

where some children died in tuberculosis epidemics and others were

shackled to beds, beaten, and raped.

Brave

Heart did her most important research near the Pine Ridge Reservation

in South Dakota, the home of Oglala Lakota and the site of some of the

most notorious events in Native American martyrology. In 1890, the most

famous of the Ghost Dances that swept the Great Plains took place in

Pine Ridge. We might call the Ghost Dances a millenarian movement; its

prophet claimed that, if the Indians danced, God would sweep away their

present woes and unite the living and the dead. The Bureau of Indian

Affairs, however, took the dances at Pine Ridge as acts of aggression

and brought in troops who killed the chief, Sitting Bull, and chased the

fleeing Lakota to the banks of Wounded Knee Creek, where they

slaughtered hundreds and threw their bodies in mass graves. (Wounded

Knee also gave its name to the protest of 1973 that brought national

attention to the American Indian Movement.) Afterward, survivors

couldn’t mourn their dead because the federal government had outlawed

Indian religious ceremonies. The whites thought they were civilizing the

savages.

Today, the Pine Ridge

Reservation is one of the poorest spots in the United States. According

to census data, annual income per capita in the largest county on the

reservation hovers around $9,000. Almost a quarter of all adults there

who are classified as being in the labor force are unemployed. (Bureau

of Indian Affairs figures are darker; they estimate that only 37 percent

of all local Native American adults are employed.) According to a

health data research center at the University of Washington, life

expectancy for men in the county ranks in the lowest 10 percent of all

American counties; for women, it’s in the bottom quartile. In a now

classic 1946 study of Lakota children from Pine Ridge, the

anthropologist Gordon Macgregor identified some predominant features of

their personalities: numbness, sadness, inhibition, anxiety,

hypervigilance, a not-unreasonable sense that the outside world was

implacably hostile. They ruminated on death and dead relatives. Decades

later, Mary Crow Dog, a Lakota woman, wrote a memoir in which she cited

nightmares of slaughters past that sound almost like forms of collective

memory: “In my dream I had been going back into another life,” she

wrote. “I saw tipis and Indians camping ... and then, suddenly, I saw

white soldiers riding into camp, killing women and children, raping,

cutting throats. It was so real ... sights I did not want to see, but

had to see against my will; the screaming of children that I did not

want to hear. ... And the only thing I could do was cry. ... For a long

time after that dream, I felt depressed, as if all life had been drained

from me.”

Brave Heart’s subjects

were mainly Lakota social-service providers and community leaders, all

of them high-functioning and employed. The vast majority had lived on

the reservation at some point in their lives, and evinced symptoms of

what she called unmourned loss. Eighty-one percent had drinking

problems. Survivor guilt was widespread. In a study of a similar

population, many spoke about early deaths in the family from heart

disease and high rates of asthma. Some of her subjects had hypertension.

They harbored thoughts of suicide and identified intensely with the

dead. Brave Heart quoted a Vietnam vet, who said: “I went there prepared

to die, looking to die, so being in combat, war, and shooting guns and

being shot at was not traumatic to me. That was my purpose and my reason

for being there.”

American Indians

suffer shockingly worse health than other Americans. Native Americans

and native Alaskans die in greater proportions than other racial or

ethnic groups in the country, from homicide, suicide, accidents,

cirrhosis of the liver, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. Public health

officials point to a slew of socioeconomic factors to explain these

disparities: poverty, unemployment, lack of health insurance, cultural

barriers, discrimination, living far from decent grocery stores.

Sociologists cite the disintegration of families, the culture of

poverty, perpetual conflict with mainstream culture, and, of course,

alcoholism. The research on multigenerational trauma, however, offers a

new set of possible causes.

At the

frontier of this research lies a very delicate question: whether some

people, and some populations, are simply more susceptible to damage than

others. We think of resilience to adversity as a function of character

or culture. But as researchers unravel the biology of trauma, the more

it seems that some people are likelier to be broken by calamity while

others are likelier to endure it.

For

instance, studies comparing twins in which one twin developed PTSD

after trauma, and the other never had the bad experience and therefore

never received the diagnosis, have uncovered shared brain structures

that predispose them to traumatization. These architectural anomalies

include smaller hippocampuses—which reduce the brain’s ability to manage the neurological and hormonal components of fear—and

an abnormal cavity holding apart two leaves of a membrane in the center

of the brain, an aberration that has been linked to schizophrenia,

among other disorders. Researchers have further identified genetic

variations that seem to magnify the impact of trauma. One study on the

mutations of a certain gene found that a particular variation had more

of an “orchid” effect on African Americans than on Americans of European

descent. The African Americans were more susceptible than the European

Americans to PTSD if abused as children and less susceptible if not.

Another

theory, even more uncomfortable to consider, holds that a particular

parental dowry may drive a person to put herself in situations in which

she is more likely to be hurt. Neuropsychologists have identified

heritable traits that push people toward risk: attention deficits, a

difficulty articulating one’s memories, low executive function or

self-control. The “high-risk hypothesis,” as it is known, sounds a lot

like blaming the victim. But it isn’t all that different from saying

that people have different personalities and interact with the world in

different ways. As Yehuda puts it, “Biology may help us understand

things in a way that we’re afraid to say or that we can’t say.”

In

the past few years, Yehuda has helped design and has co-authored

studies with Cindy Ehlers, a neuroscientist at La Jolla’s Scripps

Research Institute, along with others, who advanced the high-risk

hypothesis for Native Americans. A host of studies have shown that

significantly more American Indians endure at least one traumatic

incident—assault, an accident, a rape—than

other Americans (among the subjects in this particular study, the rate

was 94 percent); that the risk of being assaulted and contracting PTSD

seem heritable to about the same degree (30 to 50 percent); and that

trauma, substance abuse, and PTSD mostly seem to happen in early

adulthood. “What is being inherited in these studies is not known,”

writes Ehlers. But the fact that all these bad things emerge at the same

point in the kids’ development argues for some degree of genetic or

epigenetic influence. Another way of saying it is that maybe these young

adults are finding themselves at the center of a particularly cruel

collision of genes and history.

On

the stormy afternoon in July when I visited Tom Sun’s apartment,

lightning had just blown out a transformer drum down his block and the

lights were out. The sky was just bright enough to illuminate a domestic

idyll: A two-year-old boy bounced happily on and off Sun’s lap. A

ten-year-old girl whisked the toddler into the kitchen as soon as her

father asked her to. The living room was sparsely but pleasantly

furnished. The air of calm was no accident. Now in his late thirties,

Sun is a counselor to teenagers in trouble, including gang members, and

has arranged his schedule so that he can come home early every day and

give his children the care he was denied. (Sun’s wife works late.) In

addition to cultivating serenity, he teaches them self-reliance. He

wants them, he tells me, to be prepared for whatever reversals of

fortune they may encounter. He has taught them to cook for themselves,

“just in case something should happen to Mommy and Daddy”; he has taken

them for 15-mile walks to a mall over the border in New Hampshire so

they know they can walk that far if they need to. It’s hard to imagine

many other Americans doing this and hard for me not to interpret Sun’s

precautions as echoes of his mother’s experience. But it is his way of

mastering the past.

Ever since

humans have been inflicting violence on other humans, they have been

devising techniques to deal with its aftereffects. The French

phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty writes of “the lived body”—the

body as a receptacle of past experiences, of a knowing that bypasses

knowledge. Think of a culture as a collective lived body, the scars of

its experiences accumulated over generations and fixed into rituals and

mores. A less elegant way of putting this is in the language of therapy:

culture as coping mechanism.

The

Jewish mode of trauma management is commemoration. An old joke has it

that all Jewish holidays amount to the same thing: “They tried to kill

us. They failed. Let’s eat!” When Jews retell the tales of Egyptian

slavery—hunger, humiliation, murder—they’re

performing acts of catharsis in the company of others whose forebears

also outlasted their tormentors. If refugees from the Nazis and their

offspring have thrived relative to other victims of massive historical

trauma, surely that has to do with the quantity of cultural and human

capital that washed up with the survivors on the shores of America and

Israel. But their flourishing may also be a therapeutic benefit of

ritualized communal mourning. It is no accident that the Holocaust now

has its own holy day: Yom Ha-Shoah, the Day of the Holocaust.

Cambodians

don’t privilege commemoration in the same way, although they certainly

have rituals for mourning the dead. Dwelling upon the atrocities of the

Khmer Rouge, I was told repeatedly, is not the Cambodian way. During my

time in Lowell, I visited a wat,

a Buddhist temple, and met a monk who explained, through a translator,

that he advises people who come to him for help to accept what cannot be

changed, focus on the future, and trust that all injustices will come

out right in the end.

Looking

insistently forward, rather than backward, may strike some Westerners as

a form of denial. That reliving the past and telling tales about it

offer the best cures for mental suffering must qualify as the most

entrenched belief in Western psychology, with deep roots in the

Christian imperative to confess and the Jewish injunction to remember.

Delve into the literature on collective trauma, and you will read about

the devastating and long-lasting suffering occasioned by “the conspiracy

of silence,” the failure to speak openly about the horrors of recent

history.

This ingrained faith in

memory has surely influenced the most common treatment for PTSD:

cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT. The dominant CBT protocol for PTSD

is prolonged exposure—the vivid reexperiencing

or reimagining, and in some cases writing down, of distressing memories,

until they have been crafted into narrative and lost their sting. By

creating new associations and contexts for the intrusive thoughts, the

therapy is said to decouple memory and fear, along with all the

physiological reactions that fear provokes.

But

repeated reexperiencing does not work in all cases. For some people,

rather than healing, it may retraumatize. Anthropologist and

psychiatrist Devon Hinton, who works at Arbour Counseling, talks about

his patients’ “catastrophic cognitions”—extreme

attacks of anger, say, triggered by experiences that set off memories,

which then kickstart fits of anxiety, and so on. These triggers often

have deep cultural and historical associations. They may be children

behaving in a manner deemed disobedient or ungrateful; they may be, as

Lemar Huot, a young therapist at Arbour (she treats Sandy, among others)

explained to me, women refusing to act as they would have in the old

country. Being disrespected, Hinton told me, reawakens the sensation of

being coldly demeaned by the Khmer Rouge. Symptoms such as neck pains

and shortness of breath may reenact suffering endured during the years

of slavery, when Cambodians were sometimes forced to carry heavy loads

on their heads and shoulders or were tortured by near-drowning or having

bags placed over their heads. Huot recounted the tale of a beloved

grandmother who began to behave in a way that left no room for

ambiguity. “We’d come home from school,” said Huot. “We lived across the

street from a baseball field, and she’d be in it. She’d hidden a bag of

rice in her clothes and told us it was time to run. Or she’d start

seeing bugs in her food.”

Hinton is

part of a group that has catalogued more enigmatic sources of distress;

they have even succeeded in having them included in the DSM-V. The

manual includes nine culturally specific presentations of mental

disorders; one is Cambodian, others are Latino, Japanese, and Chinese.

The Cambodian one is the “khyal attack.” Khyal

is thought to be a sort of malevolent wind that can wreak havoc in the

body, blinding and even killing. Outbreaks occur when the flow of khyal

is trapped in the body; this may lead to cold limbs, dizziness, heart

palpitations, tinnitus, and blurry vision, among other things. The fear

that one is suffering a khyal attack is another “catastrophic cognition,” a terror born of terror that keeps cycling back on itself.

Another

source of what feels like near-fatal anxiety is sleep paralysis,

idiomatically known to Cambodians as “the ghost pushes you down.” This

is when a person wakes but is unable to move and senses the presence in

the room of a menacing figure. You might call sleep paralysis a

haunting. Visitations often begin during periods of everyday stress—money

troubles or fights with children or spouses. The guests are understood

to be the angry spirits of people of whose gruesome deaths the dreamer

may, say, have witnessed: fellow villagers whose skulls were smashed, a

child killed by being swung against a tree, a friend who starved to

death. Apparitions of the unburied and unmourned can dislodge a soul

from its body and enslave the visitant to the ghost. The only way to

allay its fiendish malignity is to make gifts and offer incense in the

name of the dead.

Hinton argues that

treatments should focus as much, if not more, on techniques for calming

oneself down than on awakening demons and that these should be rooted

in the patient’s own traditions. For his clients, he uses meditation,

mindfulness, stretching, the visualization of images that promote

self-forgiveness and loving-kindness. For instance, Buddhism prizes a

quality called upekkha (the word comes from

Pali, an ancient Indian language): equanimity. This entails distancing

oneself from emotions and disturbing thoughts; a Buddhist metaphor is to

think of them as clouds in the sky, and let them scud away, and so that

is something practitioners of culturally adapted CBT might have people

do. “We have Southeast Asian patients imagine love spreading outward in

all directions like water,” writes Hinton. “This is because in Buddhism

water and coolness are associated with values of love, kindness,

nurturing, and ‘merit-making,’” that is, doing good deeds such as giving

to the poor or to the temple.

I do

not mean to imply that a traumatized nation should forgo a strict

accounting of the crimes of the past. One source of deep anger for many

Cambodians is that the Khmer Rouge regime ended inconclusively. Only

this autumn, nearly 40 years after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, did a

United Nations–backed tribunal open hearings on whether its top

officials committed genocide; before that, only a handful of officials

had been tried and sentenced on the lesser charge of crimes against

humanity. The director of the most notorious torture center, Kaing Guek

Eav, better known as “Duch,” was only given a lifetime sentence after

Cambodians protested his lighter penalty of 35 years. Cambodia’s current

prime minister, Hun Sen, was at one point a Khmer Rouge commander,

though he left the group when Pol Pot began killing his own followers.

Sen is now a capitalist rather than an agrarian communist, but his

government is authoritarian and certainly does not give the reassuring

sense that the past is safely past.

So

it is important to remember. But tone also matters. What made Yehuda

the saddest while cataloguing the stories of survivors’ children, she

told me, were the descriptions of childhood homes that felt like

graveyards and the children’s sense that laughter desecrated the memory

of the dead. Death, she says, must not quash life: “Living and laughing

and being joyous and almost disrespectful to those who suffered—it’s what they’d want you to do, without forgetting them,” she says.

When

entire countries or communities are ravaged by the effects of massive

collective trauma, often the response is to call for truth commissions

and reparations. Although these deliver necessary justice and restore

moral balance to the world, they don’t suffice to heal the damage.

Studies of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for

instance, indicate that, though it imparted a greater knowledge of

history among South Africans, it had little impact on their well-being.

The

emerging research on trauma makes it increasingly clear that in order

to interrupt the cycle of dysfunction for families, we’ll have to

address the biological aftershocks of trauma. There are hopes for quick

fixes—drugs and other rapid treatments to

prevent the traumatized from developing PTSD. Early research on mice

into a non-addictive drug called SR-8993, for instance, appears

promising: It activates opioid receptors in the amygdala, which may

prevent the consolidation of fearful memories. This suggests that

perhaps there’s a way to keep the traumatized from becoming fixed inside

their terrors.

As for those who

already have PTSD, some scientists swear by beta-blockers. They are said

to interfere with the storage of memories—to

blunt the emotional edge of horrific memories and to help the brain

extinguish fear by making its circuits a little more flexible and

associations less fixed. However, beta-blockers haven’t done any better

than placebos in recent tests. “Fear extinction is a lovely theory, and

if it were really about fear, it would be nice to extinguish it,” says

Yehuda. But “in people fear is just one of many things that happens when

you’re traumatized.” Yehuda puts more stock in hydrocortisone, which

inhibits the abnormal cortisol secretion that permanently damages the

body’s ability to quell anxiety.

None

of this tells us specifically what to do for the next generation.

Perhaps one of the most popular approaches emerges from social work and

public health: It is to help mothers with PTSD deal with their infants

so that they don’t reproduce their angst in their young children. I can

no longer count how many psychologists I talked to who are launching or

already working on programs that try to do this, sometimes starting

during pregnancy. Another idea is to run genetic tests on the recently

traumatized, so as to identify who among them is more likely to develop

PTSD (and thus, presumably, to pass it on). Trauma victims in an

emergency room in Atlanta who tested positive for genes associated with a

risk of PTSD got an hour of psychotherapy, with follow-up over the next

two weeks. They developed fewer symptoms than victims with a similar

profile who did not get the therapy.

Yehuda,

for her part, aims to locate the exact spots on genes where molecular

changes occur in response to trauma. Such knowledge could elevate

interventions to an even higher level of precision than genetic

screening. To be effective, she says, “we have to understand what are

the reversible and the non-reversible targets,” by which she means, what

can be restored to normal and what can’t be. This research, however, is

not easy, because among other dangers you risk trying to reverse

something that actually helps a body adapt—of mistaking resilience for pathology, as she puts it. Nor are these investigations cheap.

It

seems a small moment of grace when you hear a tale of how the past can

come to heal rather than bedevil. Lemar Huot is grateful that her

parents and grandmother, who were able to carry on and to shield her

from their experiences until her grandmother became sick, never

inculcated in her any fear of the dead. On the contrary, “it was almost

reassuring to have them visit,” she says. “There was this idea that your

loved ones are never far away.” But the collective wounds of the

Cambodian community have a way to go before they close up, and at some

level, of course, they never will. Huot discerns a lingering anomie

among her patients and their children. Children learn from their

parents’ ongoing torment that the past is unpalatable and the present a

flimsy gauze that can easily be torn to expose the festering underneath.

There

is biological PTSD, and familial PTSD, and cultural PTSD. Each wreaks

damage in its own way. There are medicines and psychotherapies and the

consolations of religion and literature, but the traumatized will never

stop bequeathing anguish until groups stop waging war on other groups

and leaving members of their own to rot in the kind of poverty and

absence of care that fosters savagery. All that, of course, is

improbable. The more we know about trauma, though, the more tragic that

improbability becomes.

Subscrever:

Comentários (Atom)

%2Bsearching%2Bfor%2Bfood%2Bon%2Balgae%2Bin%2Bthe%2BNorth%2BEast%2BAtlantic%2BOcean%2B(Gulen%2C%2BNorway).jpg)

.jpg)