Many species are already critically endangered and close to

extinction, including the Sumatran elephant, Amur leopard and mountain

gorilla. But also in danger of vanishing from the wild, it now appears,

are animals that are currently rated as merely being endangered:

bonobos, bluefin tuna and loggerhead turtles, for example. In each case, the finger of blame points directly at human

activities. The continuing spread of agriculture is destroying millions

of hectares of wild habitats every year, leaving animals without homes,

while the introduction of invasive species, often helped by humans, is

also devastating native populations. At the same time, pollution and

overfishing are destroying marine ecosystems.

“Habitat destruction, pollution or overfishing either kills off wild

creatures and plants or leaves them badly weakened,” said Derek

Tittensor, a marine ecologist at the World

Conservation

Monitoring Centre in Cambridge. “The trouble is that in coming decades,

the additional threat of worsening climate change will become more and

more pronounced and could then kill off these survivors.”

The problem, according to Nature, is exacerbated because of

the huge gaps in scientists’ knowledge about the planet’s biodiversity.

Estimates of the total number of species of animals, plants and fungi

alive vary from 2 million to 50 million. In addition, estimates of

current rates of species disappearances vary from 500 to 36,000 a year.

“That is the real problem we face,” added Tittensor. “The scale of

uncertainty is huge.”

In

the end, however, the data indicate that the world is heading

inexorably towards a mass extinction – which is defined as one involving

a loss of 75% of species or more. This could arrive in less than a

hundred years or could take a thousand, depending on extinction rates.

The Earth has gone through only five previous great extinctions, all

caused by geological or astronomical events. (The Cretaceous-Jurassic

extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago was

triggered by an asteroid striking Earth, for example.) The coming great

extinction will be the work of Homo sapiens, however.

“In the case of land extinctions, it is the spread of agriculture

that has been main driver,” added Tittensor. “By contrast it has been

the over-exploitation of resources – overfishing – that has affected

sealife.” On top of these impacts, rising global temperatures threaten

to destroy habitats and kill off more creatures.

This change in climate has been triggered by increasing emissions –

from factories and power plants – of carbon dioxide, a gas that is also

being dissolved in the oceans. As a result, seas are becoming more and

more acidic and hostile to sensitive habitats. A third of all coral

reefs, which support more lifeforms than any other ecosystem on Earth,

have already been lost in the last few decades and many marine experts

believe all coral reefs could end up being wiped out before the end of

the century.

Similarly, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles and a

seventh of all birds are headed toward oblivion. And these losses are

occurring all over the planet, from the South Pacific to the Arctic and

from the deserts of Africa to mountaintops and valleys of the Himalayas.

A blizzard of extinctions is now sweeping Earth and has become a fact

of modern life. Yet the idea that entire species can be wiped out is

relatively new. When fossils of strange creatures – such as the mastodon

– were first dug up, they were assumed to belong to creatures that

still lived in other lands. Extant versions lived elsewhere, it was

argued. “Such is the economy of nature,” claimed Thomas Jefferson,

who backed expeditions to find mastodons in the unexplored interior of America.

Then the French anatomist Georges Cuvier showed that the

elephant-like remains of the mastodon were actually those of an “espèce

perdue” or lost species. “On the basis of a few scattered bones, Cuvier

conceived of a whole new way of looking at life,” notes Elizabeth

Kolbert in her book,

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. “Species died out. This was not an isolated but a widespread phenomenon.”

Since then the problem has worsened with every decade, as the Nature

analysis makes clear. Humans began by wiping out mastodons and mammoths

in prehistoric times. Then they moved on to the eradication of great

auks, passenger pigeons – once the most abundant bird in North America –

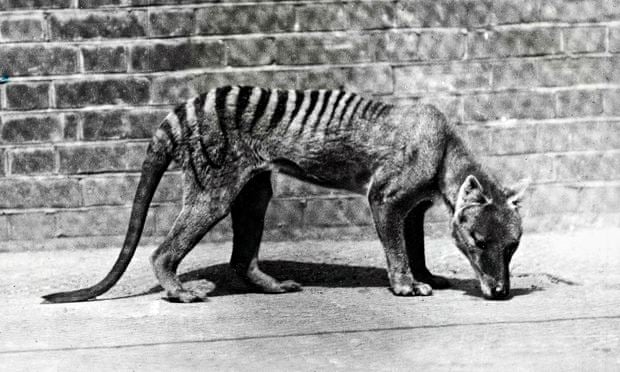

and the dodo in historical time. And finally, in recent times, we have

been responsible for the disappearance of the golden toad, the thylacine

– or Tasmanian tiger – and the Baiji river dolphin. Thousands more

species are now under threat.

In an editorial, Nature argues that it is now imperative

that governments and groups such as the International Union for

Conservation of Nature begin an urgent and accurate census of numbers of

species on the planet and their rates of extinction. It is not the most

exciting science, the journal admits, but it is vitally important if we

want to start protecting life on Earth from the worst impacts of our

actions. The loss for the planet is incalculable – as it is for our own

species which could soon find itself living in a world denuded of all

variety in nature. As ecologist Paul Ehrlich has put it: “In pushing

other species to extinction, humanity is busy sawing off the limb on

which it perches.”